MICRO WRITING EXAMPLESCLANDESTINE MESSAGING |

| Words Within Words: Draft of Declaration of Independence Reveals its Secret. |

On this page, you can see example images of covert messages that have been done in Micro Writing. I've put them together as a result of not so much a request but a statement made by sparring partner Nick Pelling of CipherMysteries. Nick has made it clear that his position is that there is no micro writing on the Somerton Man Code page and that even if it was it would have nothing to do with the Somerton Man Case, echoes of Professor Derek Abbott methinks. Another statement made was that he suspected that no one has seen any examples of covert micro writing. Interesting that he has reached his firmly voiced opinions without carrying out any research apparently. Also of interest is that he has failed to produce any evidence to substantiate his arguments.Well, you can sit back now Nick and view some more examples, in addition to the Somerton Man Code and Jestyn's Verse 70 Inscription, of covert micro writing from Denmark, China, Germany and the USA. I'll be adding more as they come to hand and in the meantime, enjoy!

US Library of Congress: The Smudges Reveal the Secret

First off here's a most interesting image, it's a repeat of the header image. It is a close up of a part of the draft of the American Declaration of Independence. this image was taken to show how a research Scientist from the US Library of Congress was able to recover a long hidden word that lay in a 'smudge' mark on the draft.Whilst this isn't a covert use of micro writing it is very relevant to the Somerton Man Code, the methods used by the scientist are well in advance of the ones used here and thankfully the letters and numbers we have recovered were considerably easier to find.

The Bronte Sisters: History and Recovery Techniques (Thanks to Pete Bowes for passing this link on: http://news.harvard.edu/

(See Highlighted Section Below Re Recovery Method)

Flames of childhood passion often die. How many astronauts and ballerinas are among us? Yet some talent is so profound that even early efforts signify genius.

The tiny, hand-lettered, hand-bound books Charlotte and Branwell Brontë made as children surely qualify. Measuring about 2.5 by 5 centimeters, page after mini-page brims with poems, stories, songs, illustrations, maps, building plans, and dialogue. The books, lettered in minuscule, even script, tell of the “Glass Town Confederacy,” a fictional world the siblings created for and around Branwell’s toy soldiers, which were both the protagonists of and audience for the little books.

In 1829 and 1830, Charlotte and Branwell cobbled the pages together from printed waste and scrap paper, perhaps cut from margins of discarded pamphlets. They wrote with steel-nibbed pens, which tend to blot, yet the even script demonstrates their practiced hand.

Charlotte, who in adulthood wrote “Jane Eyre,” nested leaves together, then neatly sewed the spine with embroidery thread; it’s evident she constructed her book and planned its content before ever putting pen to paper. Branwell, who would become a painter and poet, stacked folded leaves together, which allowed him to add pages as he needed; clearly not as adept with needle and thread as his sister, he stab-sewed the leaves together with thicker linen yarn.

Children can be rough on their playthings — miniature books created by the younger Brontë siblings Emily and Anne did not survive — but Charlotte kept and stored the “Glass Town” adventures carefully. “They must have been very precious to them, as they are to us today,” said Priscilla Anderson of Harvard’s Weissman Preservation Center, who restored the volumes.

Only about 20 volumes of Brontë juvenilia are known to remain. Harvard holds nine, the Brontë Museum at the family home in England owns a few, and the remaining are scattered among museums and private collectors.

Until recently, juvenilia — works produced by an author or artist while still young — were viewed as oddities by scholars and collectors. Today they are understood to provide valuable and rare insight into an author’s development. In the case of the Brontës, experts might trace Gothic influences from the 13-year-old Charlotte’s stories, or identify Branwell’s growth as an artist by comparing his childhood illustrations and his later paintings. Perhaps even more importantly, the books provide a glimpse into the inner lives of children growing up in a society in which they were expected to be seen and not heard.

“What is extraordinary is the extent to which they imitated a professional publication, the variety of the content, and the perseverance it required,” said Anderson. “The ability to make these volumes from start to finish out of scraps is impressive.”

At nearly 200 years old, the books are delicate. Over time, the paper became increasingly fragile, the adhesive used to mount the volumes damaged the covers, and the tiny script was hard for scholars to read. To ensure that scholars today and tomorrow have access to these treasures, the library repaired, rehoused, and digitized the books. Their unusual size, age, and nature presented several challenges to Anderson and Debora Mayer, the Helen H. Glaser Conservator at Weissman.

“Perhaps children’s eyes and hands can read and manipulate these things, but for grownups they’re microscopic,” explained Anderson, who said she felt like she had giant’s hands when she worked on the books.

To repair tears, Anderson used fine surgical instruments, teasing out and pasting down individual fibers of kozo paper about the width of a human hair. (Kozo is a fine paper made from the inner bark of an Asian plant, and is regularly used to mend books.) All through the painstaking work, she knew even a small mistake would be magnified. “I held my breath, literally,” said Anderson, “to keep fragments of paper from blowing away.”

New binding exposed text in the gutters of Branwell’s volumes for the first time in 170 years, and the digital technology deployed provides clarity beyond that of the human eye. Technicians moved the camera very slightly on multiple takes and combined them into one image. Every millimeter is sharply focused.

Charlotte’s husband sold the volumes after her death to a collector, who gave them to poet and fellow collector Amy Lowell; she donated the set to Houghton Library in 1925.

The digital copies of the Brontë juvenilia have largely met scholars’ needs, according to Houghton curator Leslie Morris. Yet the awe-inspiring physicality of the books as artifacts cannot be captured on screen.

“These tiny books help to evoke the whole experience of the Brontë children. Here they are, living in a somewhat isolated parsonage in Yorkshire, having only themselves as playmates and needing to entertain each other,” Morris said. “Seeing the physical object brings home the effort and intelligence it took to create them and why they created them. Having grown up with Brontë, it’s a way of connecting with the past through objects.”

The nine Brontë volumes held by Harvard referenced in this story are available in full, free, online:

By Charlotte Brontë:

Scenes on the great bridge, November 1829

The silver cup: a tale, October 1829

Blackwoods young mens magazine, August 1829

An interesting passage in the lives of some eminent personages of the present age, June 1830

The poetaster: a drama in two volumes, July 1830

The adventures of Mon. Edouard de Crack, February 1830

By Patrick Branwell Brontë:

Branwells Blackwoods magazine, June 1829

Magazine, January 1829

Branwells Blackwoods magazine, July 1829

WW2 Danish Example

This is an image of covert microwriting, part of a collection in a Danish museum. The note was one of a number apparently written by prisoners held in a German Labour camp and then smuggled out. Good example of the skill, notice how thin and wispy the individual letters can be.

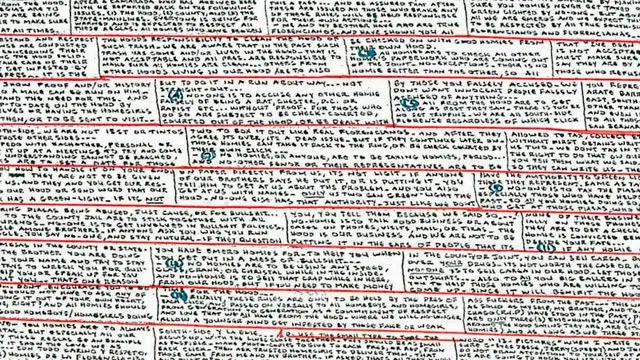

Example of Covert Microwriting From Recent Years

This is an example of a 'Kite' it's the form of secret microwriting used by US gangs to communicate from prisons to the outside world and back. There are many of these examples in existence; here are two. The 'Kites' are in many cases rules of behaviour whilst in others they contain instructions for a 'hit' to be carried out. Two examples are shown here.

An example from the Mexican Mafia

German Espionage Example WW1

Whilst in this example the micro message viewable takes the form of a small drawing, it is a covert message created by a WW1 German spy and it was hidden behind a postage stamp, it is of a then new kind of anti Zeppelin artillery shell:

NZ Postage Stamp

In this image set, you see not a covert message, but it is one that has been around for a couple of thousand years. It shows how messages can be hidden behind a postage stamp and in this case it's a prayer. By micro writing standards this example is quite large:

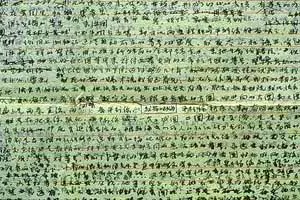

Chinese Example of Microwriting

Written by Chinese Artist MU Xin whilst imprisoned in China in the early 1970s. I can offer no translation but if anyone has that skill that would be appreciated.

In this image we see how iodine vapour is used to reveal secret writing on a handkerchief. There are cases including when in WW2 the German spy George Dasch landed on Long Island from a submarine surrendered to the FBI, he had on him a handkerchief that when treated with iodine vapour revealed the names and addresses of his contacts in the US. This is an example of of how powerful Iodine vapour could be in revealing the marks left by the writer, not fingerprints on this occasion but the same chemical has been used for that purpose.Iodine Vapour Reveals Secret Writing

This method of secret writing was later superseded by a 'dry' method. One of the issues faced by spies was that in order to write with secret inks, the process was to first steam the paper to prepare it then write the code or letter with secret ink then re-steam it to reduce or remove the indentations left by the physical action of writing and then finally, a most interesting point, they would write over the invisible ink writing with normal writing.